Lawrence, Jacob. (Between 1940 and 1941). During World War I there was a great migration north by southern Negroes [Painting]. Image Source

ID: A black and white painting of a crowd in motion wearing 40s style clothing. The Black figures are painted in a semi-abstract manor, carrying their belongings, and moving in the same direction.

My offering this month is undoubtedly that of The Great Migration. Oftentimes we celebrate Black individuals as singular contributors during this time. But perhaps this year we can take time to study the six million individuals who collectively designed the American Dream, their journeys, and the formation of Black History Month—A time when we have an opportunity to reconcile a more complete American History.

It's February again, and as we move through our annual 28 days of celebrating Black History; I find myself thinking about the hows and whys of this niche and complex celebration in American culture. As a person who identifies as Black or African American, I want to make clear connections with who I am and my work as an Applied Theatre Artist. It’s important to me that participants have an example of self awareness when leading workshops on individual and cultural identities. The beauty of Applied Theatre is that its framework is situational, with each character in the dramatizations reflecting the lived experiences of the participants. It is through my craft that I explore the pressing issues and questions on all of our minds. This month one of those questions is how did Black History Month begin? What were the events that surrounded it’s inception and why is Black History separate from general American History?

In an examination of the origins of Black History Month, I began to think back to when I was younger. I tried to remember if Black History Month had always been a part of my life. As I browsed through each year, starting around first grade, I realized the answer was a resounding yes. Not only did we celebrate Black History in February, it was perpetually acknowledged in my home, schools, community, even statues were daily reminders of the contributions of Black Americans. It was always my understanding that Black people were the foremost physical laborers and social architects of, not just the American South but, every part of what became our United States. For me, growing up in Detroit, I learned American history through the lens of the people who were on it’s frontlines. I knew the stories of women, men, and children who made countless sacrifices. Ones that spanned from the Transatlantic Slave Trade to the eventual mass migration from the American South to Northern and Midwestern cities. This collective relocation rooted in the desire for safety and survival, was a given a name, The Great Migration.

I am the grand daughter of families that made their way from Mississippi and North Carolina to Detroit for a better life. One of the most defining moments in US history, The Great Migration was an event that took place over the course of six decades. “Some six million Black southerners left the land of their forefathers and fanned out across the country for an uncertain existence in nearly every corner of America.” (Wilkerson, 2010). This “leaderless movement” was one of Black America’s greatest acts of resistance against a system of laws, discrimination, and violent acts of hatred.

Scott and Violet Arthur arrive with their family at Chicago's Polk Street Depot on Aug. 30, 1920, two months after their two sons were lynched in Paris, Texas. The picture has become an iconic symbol of the Great Migration (Chicago History Museum).

Photo taken on Aug 30, 1920: Photo Source

ID: A Black family of eight is posing for a black and white photograph. They're all wearing hats, 1920s formal wear, and holding their luggage.

In simpler terms, The Great Migration was a mass exodus of Black American citizens from the American South to escape Jim Crow laws and move to asylum cities in Northern, Midwestern, and Western states. Black Americans wanted a full life and safety as well as access to personal, social, financial, and educational freedom.

This massive movement defined the current structure of many American cities and shaped our social landscape. The history of America in it’s truest form not only includes the lived experiences and contributions of Black people, it is saturated with it. So how did we arrive at these 28 days?

When I was in middle school I learned that Black History Month started with the efforts of Dr. Carter G .Woodson, who earned his PhD in History from Harvard University. In 1915, Woodson founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History and it was through this organization that he started Negro History Week in February 1926. Woodson started this foundation and week of acknowledging Black life because he noticed the contributions of Black people being excluded from the narrative in White spaces (at the time), like the American Historical Association. After being told he couldn’t attend their conferences, Woodson decided to create an institution of his own funded by Black supporters with it’s headquarters in Chicago. The Association for the Study of Negro Life and History was committed to educating Black people, many of whom were just arriving in new cities during The Great Migration. For the first time ever, a convergence of truthful information about Black Americans started to circulate and they began to create narratives of their own.

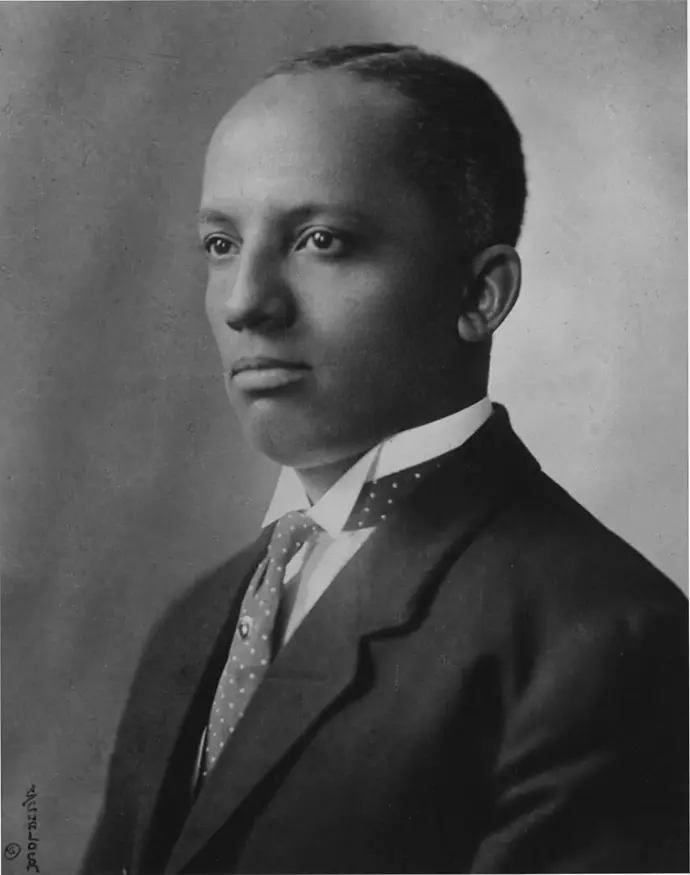

Dr. Carter G. Woodson, commonly known as The Father of Black History, "was the second Black American (only following W.E.B. Du Bois) to graduate with a PhD from Harvard and the only person of enslaved parentage to earn a PhD in History from any institution in the United States" (National Park Service).

Photo taken in 1915 by Addison Norton Scurlock: Photo Source

ID: A Black man poses stoically for the black and white photograph, looking away from the camera, and wearing a suit.

From the small percentage of Black people already living in asylum cities in the United States, came a clear call to the rest still living under Jim Crow laws. One of the clearest calls came from newspapers published in cities like Chicago, one of which was started by Woodson called The Journal of African American History. This journal and other newspapers like, The Defender were deeply instrumental in the persuasion of Southern Blacks to begin their journey towards a new life. The formation of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, with it’s commitment to centering Black history and the mass movement of The Great Migration, that landed Black people in safe places, started in the same year of 1915. Negro History Week eventually turned into a month long celebration in 1976 with the word “Negro” being replaced with “Black” in an effort to find a more appropriate term, bringing us to Black History Month.

I have more questions that I will continue to explore, but I wanted to share these initial findings as I uncover more about our collective histories and personally reconnect with my own. We all have hundreds of intersections and mine reach across my artistic, intellectual, emotional, geographical, physical, and social parts, yet, at the core, is my experience as a Black American. That experience comes through my every expression. It is simply who I am, and still these questions remain.

References:

Black History Month: A Commemorative Observances Legal Research Guide. Library of Congress. https://guides.loc.gov/black-history-month-legal-resources/history-and-overview

Gates Jr, Henry Louis & McGee, Dyllan. (Executive Producers). (2025-present). Great Migrations: A People on the Move. [TV Series]. McGee Media and Inkwell Media.

Lawrence, Jacob. (Between 1940 and 1941). During World War I there was a great migration north by southern Negroes [Painting]. Image Source

Wilkerson, Isabelle. (2010). The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration. Vintage.

Woodson, Carter G. NAACP. https://naacp.org/find-resources/history-explained/civil-rights-leaders/carter-g-woodson

Woodson, Carter G. National Park Service. National Park Service_Carter G. Woodson.

Does your school or district need support developing a curriculum, or a series of lesson plans around specific topics, skills or needs? Get in touch with THENCE using the form below.